About Ernie Pyle

Ernest Taylor Pyle grew up in Dana, Indiana, a small farming community where hard work and helping your neighbor out counted most. He was shy, thin and not well suited for farming. Leaving Dana to study at IU in 1919 would have been a relief of sorts for Pyle. It was at IU that he took a class with a professor who had traveled to Latin America, possibly spurring Pyle’s own travel lust. At IU he took his first trip out of the country to far-flung Asia as an equipment manager with the school’s baseball team. At IU, Ernie became a journalist while working at the Indiana Daily Student, eventually earning his way to editor in chief. By dedicating himself to the paper, fundraising for new campus buildings and drumming up fans as IU’s football team manager, Pyle overcame his shyness and became well known among the 2,200-plus students. Although he likely disappointed his parents by leaving campus one semester short of graduating, IU was a pivotal three-and-a-half years for Ernie.

After his first newspaper job in LaPorte, Indiana, Ernie moved to Washington to edit copy for the Washington Daily News. In 1926, chafing over their nine-to-five work grind, Pyle and his wife Jerry took off in their Ford Roadster and traveled 9,000 miles across the country. They slept in a tent alongside the road or stayed in cheap hotels. It was his first stint as the “vagabond Hoosier” and eventually led to a full-time travel column.

‘You can hardly walk down the street, or chat with a bunch of friends, without running into the germ of something that may turn up an interesting story if you’re on the lookout for it. News doesn’t have to be important, but it has to be interesting.’

–Ernie Pyle’s advice to reporters

from James Tobin’s “Ernie Pyle’s War: America’s Eyewitness to World War II”

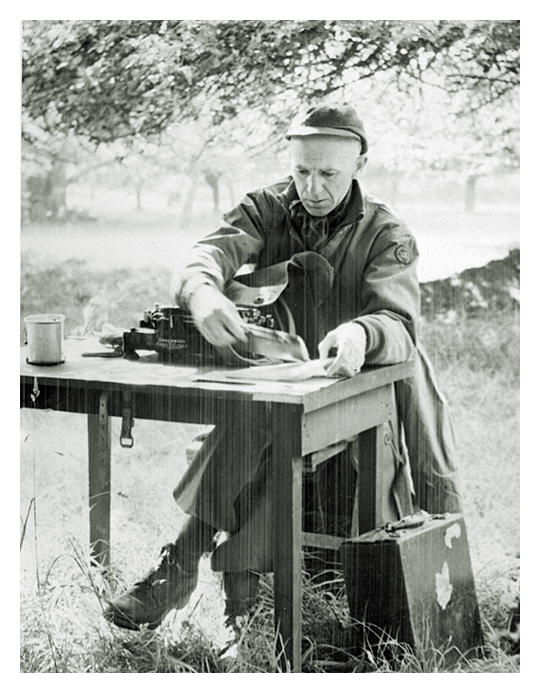

On that extended roadtrip, Pyle developed his unique travel reporting style, challenging what was then considered newsworthy. He would drive into a town and sometimes head to the local newspaper to get news tips. Other times he discovered interesting subjects through his own conversations. He would spend hours and sometimes days with his subjects observing them. He had a tremendous memory and could shape these encounters into meaningful, sometimes poignant stories. Most of Ernie Pyle’s readers loved his column because of what Pyle documentarian Todd Gould described as his ability "to see the extraordinary within the ordinary.” Pyle wrote about prospectors, farmers, school teachers, bell ringers, lepers and loggers — anyone he admired or found interesting. His years of hard work — he often wrote six 900-word columns a week — paid off during the war. The ability to find those extraordinary-within-the-ordinary stories among soldiers endeared him to families of the soldiers, as well as the GIs themselves. At the height of his popularity, as many as 30 million people read Pyle. His column on a beloved captain who had been killed in Italy during WW II, along with the columns about the Battle of Britain and the Normandy campaign, are some of his most memorable. In 1944, he earned the Pulitzer Prize. The next year he was killed while covering the war in the Pacific.

Journalism classes still read Pyle’s columns today, and IU dedicates an entire course to Pyle. Why is Pyle still relevant to students? Partly because his boots-on-the-ground, embedded style of combat reporting is credited with changing how journalists cover war. Partly, too, because of the sheer amount of material Pyle produced on a fascinating transitional period in the United States. His account of the Roaring ’20s, the Great Depression and the war provide an engaging history.

Pyle’s appeal to students lies not only in his writing, but in the behind-the-scenes messiness in his personal life. Students reading James Tobin’s biography learn about Ernie Pyle’s inner struggles, undercutting the laid-back Midwesterner persona of his columns. Tobin analyzed hundreds of personal letters Pyle wrote to his wife and family, his best friend Paige Cavanaugh and his editor Lee Miller. They reveal Pyle’s insecurities about his writing abilities, his exhaustion over non-stop deadlines, his bouts of impotency, and his guilt and frustration over having to leave behind his mentally ill wife to cover the war. The letters indicate Pyle likely suffered from undiagnosed PTSD, that he was unhealthy physically as well and smoke and drank much too much. Students also learn, through Pyle, that fame has its costs as well. Once Pyle became a celebrity, he was constantly hounded by requests from fans as well as his own news organization and the military. Pyle, who was deeply committed to the war cause, was torn at being unable to fulfill all those requests at a time before personal assistants and schedulers existed. His one helper was unable even to keep up with responding to letters. Perhaps saddest of all about Pyle, his parents loved him dearly but never truly appreciated his abilities and impact.

Although Pyle was full of complexity, his life inspires students planning to be a writer. Students who want to travel and live like vagabonds. Students who drink too much. For students who are unsure of their own abilities or suffering from their own neuroses, Pyle shows them what they can still be capable of, and reassures them the road less traveled might just be the most fulfilling.